La Ramée at JaucheletteFormer Cistercian Nunnery in Walloon Brabant

by Dr Thomas COOMANS

"It is true that the abbey of La Ramée is unique in Brabant, equally for the extent of its aspect, for its site, and for all other recommendable things."

Gallia Christiana (…), t., III, Paris, 1725, col. 604-605

Introduction :Participating in spiritual impulse of monastic orders throughout our regions during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the Cistercian order established a nunnery, in around 1215, in the valley of the Grande Gette at Jauchelette, upstream from Jodoigne. It took the name of La Ramée (Rameia). This Cistercian presence was to last for five and a half centuries, and marked the region not only spiritually but agriculturally and architecturally as well.

In spite of the suppression of monastic orders in 1796 by the French administration, this presence can still be felt today thanks to the buildings that history has preserved. They mostly served an agricultural purpose, and date back to the eighteenth century, a period when the abbey was reconstructed.

Historical surveyThe origins of the abbey of La Ramée remain uncertain; we know neither the original convent, nor the exact date of its foundation. A charter in 1212 mentions the existence of a community of Cistercian nuns at Kerkom to the Northwest of Tirlemont. This site was no doubt unsuitable and the convent was translated to Jauchelette in 1215 or 1216, on land granted by Gérard de Jauche and his daughter Helwide, the abbess of Nivelles. As an abbey La Ramée was self-supporting, although it remained under the spiritual supervision of the great abbey of Villers-en-Brabant.

In a spiritual sense, La Ramée participated in the golden age of Cistercian mysticism in Brabant in the thirteenth century. Its death register includes no less than six blessed: Agnès, Anastasie, Marguerite, Ida of Léau, Ida of Nivelles and Sapience. Mainly from the bourgeoisie of Brabant or Liège, the nuns or "ladies" committed themselves through monastic orders and lived around the cloister, celebrating the divine offices and carrying out light tasks. A scriptorium renowned for calligraphy and illumination was known to have existed at La Ramée as from the XIII century. The community, led by an abbess, also included lay sisters or "converses" who undertook more material tasks.

Temporally speaking, the young abbey formed a domain including land, woods and tithed properties in numerous surrounding villages (Perwez, Bomal, Opprebais, Glimes, Ramilies, Thorembisoul, Corbais, Noduwez, Rosières, Spy, Tavier, etc.) together with the patronage of parishes (Orsmaal, Herbais, Marilles and Piétrain). It is difficult to state the exact size of the properties, but they were sufficient to support the daily life of a small community which did not apparently exceed around fifty nuns.The Medieval history of La Ramée remains little known. Like its Cistercian sisters in Florival, Valduc, Argenton, La Cambre, Aywières, etc., it seems to have lived peacefully, experiencing periods of fervour and less enthusiasm. Thus, in 1500-1501, a major reform inspired by the abbey of Marche-les-Dames re-established monastic austerity.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, with their succession of religious and political wars, made La Ramée, like all of the other abbeys, an easy target. Twice, the nuns were obliged to leave La Ramée and live in exile at their refuge house in Namur, waiting for better times (1577 to 1591 and 1632 to 1676). The domain, which was devastated each time, had to be reorganised. During the battle of Ramilies in 1706 - one of the victories of the Duke of Marlborough over Louis XIV's troops - La Ramée was used as a military hospital.

The eighteenth century, under the Austrian regime, formed the second and last period of spiritual and temporal prosperity. The abbesses developed educational activity by receiving up to 80 children from the surrounding regions in their school.In parallel, they endowed the abbey with all of its old buildings that can still be seen today. The community scarcely exceeded twenty nuns and as many lay sisters.

After the invasion by the troops of the French Republic, the abbey was heavily taxed and then declared national property in 1796. The school was closed and the 28 Cistercian sisters were evicted. The domain itself, divided into various lots, was sold in 1799.

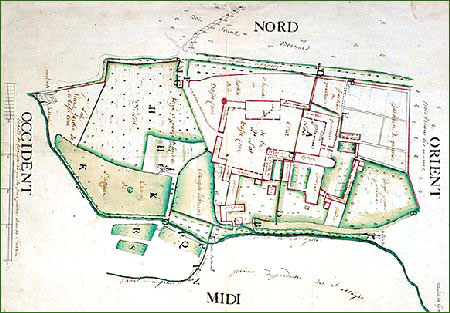

Plan of the Abbey of La Ramée before it was sold by the French administration (1799). The layout of the convent buildings and the farm can be seen, along with the hydrographic network (Indian ink and wash on paper, 52 x 73 cm. © Archives générales du Royaume, Maps and Plans, Manuscript entry n° 26211. Photo M. Wybauw).

Plan of the Abbey of La Ramée before it was sold by the French administration (1799). The layout of the convent buildings and the farm can be seen, along with the hydrographic network (Indian ink and wash on paper, 52 x 73 cm. © Archives générales du Royaume, Maps and Plans, Manuscript entry n° 26211. Photo M. Wybauw).Since then, there has been a succession of owners at La Ramée. If they completely destroyed the convent buildings (church, cloister, etc.), they maintained the farm's agricultural function.

Part of the domain belongs to the Congregation of Dames du Sacré-Cœur since 1903. The second part, or farmstead, remains the centre of one of the largest agricultural operations in the region. The farm buildings were acquired in 1990 by the S.A. Immobilière La Ramée, which developed a vast project for its restoration and use as a cultural centre.

Site and Establishment :The Grande Gette is one of the rivers that drain the rich plateau of Hesbaye, meandering through its undulated landscape. Its regular flow combined with an alteration in level that creates waterfalls capable of operating watermills, along with the presence of springs to provide clear water, undoubtedly justified the precise choice of the site for establishing the abbey. The rich lands with high yields and also the extensive woodland, far greater than it is today, guaranteed that the land given to the nuns could support their requirements.

Cistercian sites are characterised by their sufficiently hilly relief to be able to establish a complex hydrographic network and develop a vital "pre-industrial" activity there. Cartographic material from the eighteenth century reveals the presence of three watermills, a brewery and a sawmill at La Ramée.

Furthermore, the Thorembais beck, skilfully diverted a little further upstream from the confluence with the Herbais, crossed the Gette on an aqueduct and fed fishponds and pools. By means of a series of sluice gates and millraces, the two watercourses were perfectly controlled and turned the watermills all year round. Today, this complex network has been reduced to its main components and the pools have ceased to exist. A beautiful line of poplars enables the Grande Gette to be traced in a largely deforested and open landscape.

Monastic buildings :With the exception of the abbess' lodging, all of the monastic buildings at La Ramée have been destroyed. Two precious iconographic sources nevertheless make it possible to gain an idea of the configuration.

Like most monastic foundations, the straight line along which the building was established was fixed by the axis of the Church, whose chevet is turned to the East. At La Ramée, the cartography, confirmed by excavations led by the University of Brussels in 1983, identifies the precise location of the abbey church. Perfectly oriented, this single church nave construction with a polygonal chevet formed the North aisle of the cloister. The three other ranges housed the traditional monastic functions: the chapter house, the dry rooms, the parlour, the dormitory, the warming room, the refectory, kitchens, a cellar, etc.).

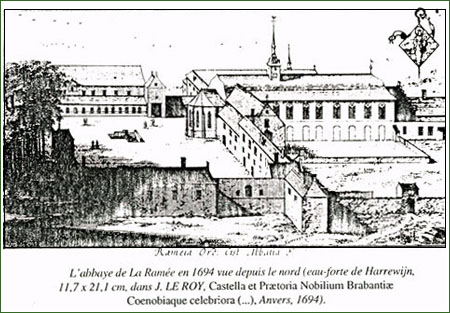

Only one picture earlier than the eighteenth century offers a view of the abbey from the North.

The Abbey of La Ramée in 1694, seen from the North (etching by Harrewijn, 11.7 x 21.1 cm, in J. LE ROY, Castella et Praetoria Nobilium Brabantiae Coenobiaque celebriora (...), Antwerp, 1694).

The Abbey of La Ramée in 1694, seen from the North (etching by Harrewijn, 11.7 x 21.1 cm, in J. LE ROY, Castella et Praetoria Nobilium Brabantiae Coenobiaque celebriora (...), Antwerp, 1694).None of the buildings shown on the engraving remains and it is scarcely possible to take the analysis much further. The regularity of the relative positions of the various wings around the courtyard confirms this impression of order and planning that is reflected in most Cistercian abbeys. A graceful little spire adds the finishing touch to the main volume of the church. A precinct wall surrounded the entire structure. The farmstead is situated to the right, beyond the scope of the engraving, such that it provides no information about any earlier layout.

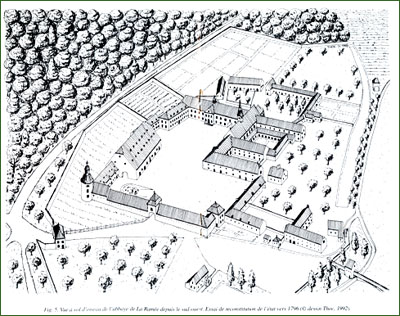

Bird's eye view of the Abbey of La Ramée from the South-West. Attempt at a reconstruction of the site circa 1796. (© dessin Thoc. 1992).

Bird's eye view of the Abbey of La Ramée from the South-West. Attempt at a reconstruction of the site circa 1796. (© dessin Thoc. 1992).A hypothetical reconstruction of the state of La Ramée at the end of the eighteenth century can be proposed by means of a plan that was used for the 1799 sale and of the remaining buildings. The small dimensions of the convent premises around the cloister, further away from the farm's huge courtyard and the broad abbess's lodging. All the constructions were entirely enclosed, by the Grande Gette and the ponds to the South, and by walls on the other sides. The gatehouse, which has now disappeared, opened out onto the road to Glimes in Huppaye.

To the NorthWest, one of the wings of the abbess's quarter escaped demolition. This two-storey brick and Gobertange stone building, covered with a hipped roof and dormer windows, has a classical façade with ten bays facing the South. The Louis XVI style door, in blue stone, is sculpted with a key in which an interesting dedication can be deciphered: aD sYDera VoLat qUae aeDIfICarI CUraVIt, meaning: "she who took the care to build goes up to heaven".

This chronogram bears the date of 1775 and thus attributes the building's construction to the abbess Séraphine Wauters, suggesting that she had died.

This chronogram bears the date of 1775 and thus attributes the building's construction to the abbess Séraphine Wauters, suggesting that she had died.Between the abbess's quarter and the grange, survives a building whose original function is unknown (school, infirmary, guesthouse) but whose style and the reference "New" buildings on the 1799 plan suggest that it was the last of the nuns' constructions before the abbey was suppressed.

The Eighteenth century Abbatial Farm :Of the building complex of the farm at La Ramée, three stand out for their volume: the porch, the dovecote tower and the monumental grange. The other constructions are shaped in long wings, all with two levels and a roof, which define the perimeter of the vast courtyard. The similarity and colour of the materials give the visible unity: brickwork with bands of Gobertange stone, sandstone blocks for the plinth and slate for the roofing. It is interesting to note that the abbey owned a Gobertange stone quarry at Mélin. All of the constructions belong to the traditional Brabant style. By means of several construction dates, the chronological approach reveals that the construction took place throughout the eighteenth century.

The vast, paved courtyard forms a space with a surface area of over a hectare. In the northwest corner, near to the stables, there is the slurry pit.

To the South, a long single-storey building with a roof and stepped dormer windows is identified as "Stables" on the 1799 plan. Dated at 1713 from the cramping, it is greatly distorted, as is the nearby turret, which housed large dovecote but was later converted into the farmers' residence. The fine carved cartouche of abbess Marguerite de Cupis, dated 1714, is a reuse.

A very long range of stables forms the western wing, at the centre of which stands the monumental porch, topped with an elegant pyramidal roof. On the eastern side of the porch, the dates 1716 and 1717 can be read, along with the coat of arms of Abbess Lutgarde de Reumont, which can also be seen on the grange. All of theses stables are currently covered with brick vaults standing on blue stone supports. Archaeological analysis reveals however that these vaults were inserted after construction, in all likelihood for fire safety reasons. The upper storey contains the hayloft.

In the northwest corner of the courtyard, the volume of the stables stands out significantly and extends right to the gable end of the grange. Outside it, a cylindrical tower was built with a complicated spired roof of three furrows of timbers which is dated 1726. The upper level of the tower served as a small dovecote as indicated on an arched window.

Most of the North side of the courtyard is occupied by the gigantic tithe barn, dated 1722, whose volume reflects the opulence of the domain. It was used to store the harvest of the tithes that tax collectors received from the abbey farms at Jauchelette, Jandrenouille, La Ramée, Mélin, Noville-sur-Mehaigne and Piétrain. This vast, long barn (49 x 22.5m) has no less than four aisles and nine bays. The storage space is divided by a crosswall and by the cylindrical brick piles which support the roof timbers. These timbers are no longer original, after a fire completely destroyed the barn on 7th March 1932: the original structure made by oakwood was replaced by oregon wood.

The L-shaped building that encloses the courtyard to the Southwest was used, according to the 1799 plan, as a farmers' lodging and cattle stables. Formerly located in the prolongation of the church, the farmhouse had a doorway in blue stone, on its northern side, to the right of a little axial frontispiece, whose accolade arch crosspiece is carved with the date 1764. The coat of arms of the abbess Louise Toussane crowns this beautiful door. The rear side overlooks a small walled garden. Returning to the courtyard from the farm, the building contained spacious stables with eight bays and three aisles, whose vaults were supported by monolithic blue stone columns. Here, the sturdy vaults date from the same period as the construction itself and constitute a perfectly implemented technical solution compared with the later added vaults in the western stables. Forming a sealed barrier covered with sand and tiles, the vaults would have prevented any potential fire in the hayloft from reaching the stables and conversely, prevent the gases from the animal housing from fermenting the content of the hayloft. Part of the exterior pointing on this building is "in red" and traces of reddish wash can still be seen, which suggests a far more contrasting visual presence than the other buildings.

Outside the courtyard, towards the South, a small building still remains which was used as an bakehouse and a wing of the brewery, together with the remains of one of the watermills on the Grande Gette.

The Nineteenth and Twenty century constructions : Ground plans of the Abbey of La Ramée

Ground plans of the Abbey of La RaméeIf a large part of the monastic buildings were destroyed following the dissolution of the abbey, the domain, which since then has been divided into separate lots, did not take long to reorganise, especially the recent constructions.

A: State in 1799, in black. The buildings that have disappeared.

Ground plans of the Abbey of La Ramée.

Ground plans of the Abbey of La Ramée.B: State in 1992, in black, the buildings constructed in the XIX and XX centuries (© dessins Thoc, 1992).

The farm retained its agricultural function and it was only around forty years ago that part of its elements had their usage changed as a result of the mechanisation of operations. The main changes to take place during the early twentieth century were the restoration of the farmhouse, the construction of a small barn against the former brewery and the establishment of several lean-to hangars.

The eastern part of the domain, after having housed a sugar refinery between 1837 and 1844, undoubtedly in the former church, became a comfortable country mansion. Facing the former abbess's lodging, on the very site of the convent premises, a pleasant landscaped garden was laid out with a large pool. In order to separate the residence from the farm, a large glasshouse was built crossways with two pavilions at either end. Two other pavilions, in the same crenellated and tiered style, were constructed at the entrance to the property, along with the small greenhouses next to the former bake house.

The establishment of the sisters of the Sacred Heart in this part of the domain in 1903 led to further constructions. The nuns built a single-aisle chapel extending from the former abbess's lodging in 1910 and replaced the large glasshouse with a utilitarian building. More recently, in 1970, two buildings intended to house retreatants were constructed alongside to the NorthWest.

Further to a Royal Decree dated 27 February 1980, the farm was listed as a historic monument and the entire domain as a landscape.

Conclusion :In spite of the disappearance of the former monastic buildings, La Ramée remains one of the most significant vestiges of the Cistercian presence in Brabant: a small nunnery combined with a major agricultural concern, located in a judiciously chosen site. With its traditional, harmonious and monumental Brabant style, this eighteenth century architectural complex is unquestionably a local heritage landmark in the Jodoigne area.

Further reading : (in chronological order)

- TARLIER, J. and WAUTERS, A., Géographie et histoire des communes belges. La Belgique ancienne et moderne. Province de Brabant, Canton de Jodoigne, Brussels, 1872, p. 67-73.

- PLOEGAERTS, Th., Les moniales cisterciennes dans l'ancien Roman-Pays de Brabant, 2, Histoire de l'abbaye de La Ramée (Rameia) à Jauchelette, Brussels, 1925.

- BROUETTE, E., La Ramée à Jauchelette. In: Monasticon belge, 4, Province de Brabant, Gembloux, 1967, p.469-490.

- DESPY, G. and UYTTENBROECK, A., Inventaire des archives de l'abbaye de La Ramée à Jauchelette (Inventaire analytique des archives ecclésiastiques du Brabant, Abbayes et chapitres, 4), 2 fasc., Brussels, Archives Générales du Royaume, 1970-1975.

- NANDRIN, J.-P., La Ramée. In: Abbayes de Belgique, Guide groupe Clio 70, Brussels, 1973, p.458-467.

- Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique, 2, Province de Brabant, Arrondissement de Nivelles, Liège, 1974, p. 223-228.

- GUYOT, Gl., L'ancienne abbaye de La Ramée. In: Brabant, 1978, Brussels, p. 8-15.

- Hesbaye namuroise (Architecture rurale de Wallonie ), edit. L.Fr. GENICOT, Liège, 1983 in particular p. 135 and 138.

- DE WAHA, M. and VAN OETEREN, V., Fouilles médiévales. Jauchelette, abbaye de La Ramée. In: Annales d'Histoire de l'Art et Archéologie, 6, Brussels, 1984, p. 109-110.

- GAZIAUX, J.-J., Parler wallon et vie rurale au pays de Jodoigne à partir de Jauchelette (Bibliothèque des cahiers de l'Institut de linguistique de Louvain, 38), Louvain-la-Neuve, 1987, p. 108-114 and 190-197, figs. 36-42.

- Hesbaye brabançonne et pays de Hannut ( Architecture rurale de Wallonie ), edit. L.Fr. GENICOT, Liège, 1989.

- VERHELST, D. and VAN ERMEN, Ed., De cisterciënzerinnen in het hertogdom

Brabant. In: Bernardus en de Cisterciënzerfamilie in België, 1090-1990, edit. M. SABBE, M. LAMBERIGTS and F. GISTELINCK, Louvain, 1990, p. 271-293.

- COOMANS, Th., Le Patrimoine rural cistercien en Belgique. In: L'Espace cistercien (Mémoires de la section d'archéologie et d'histoire de l'Art, 5), edit. L. PRESSOUYRE, Paris, CTHS, 1994, p. 281-293.

- COOMANS, Th., Cistercian Nunneries in the Low Countries: The Medieval Architectural Remains. In: Studies in Cistercian Art and Architecture, edit.M.P.LILLICH, Kalamazoo, Cistercian Publications, 2001 (forthcoming).